Itch Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Polly Farquhar

All Rights Reserved

HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

www.holidayhouse.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Farquhar, Polly, author.

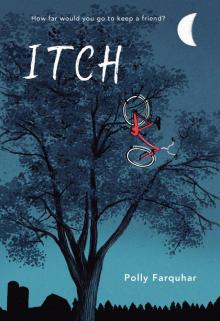

Title: Itch / by Polly Farquhar.

Description: First edition. | New York : Holiday House, [2020] | Audience: Ages 8–12 | Audience: Grades 4–6 | Summary: Ohio sixth-grader Isaac “Itch” Fitch strives to fit in, but everything seems to be going wrong, even before a school lunch trade sends his best friend, Sydney, to the hospital. Identifiers: LCCN 2019022610 | ISBN 9780823445523 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780823446346 (epub)

Subjects: CYAC: Friendship—Fiction. | Middle schools—Fiction.

Schools—Fiction. | Food allergy—Fiction. | Itching—Fiction. | Family life—Ohio—Fiction. | Ohio—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.F3676 Itc 2020 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022610

Hardcover ISBN 9780823445523

Ebook ISBN 9780823446346

v5.4

a

For my daughters

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Acknowledgments

About the Author

CHAPTER 1

THE DAY THE tornado came through, Sydney, Nate, and I were out riding our bikes together, burning down the banks of the river and then splashing into the water. The river was wide, slow, and muddy. The grass in the yards had turned a crunchy kind of yellow and the corn in the field that stood between us and the gas station was taller than even Nate. It was August. School started next week. Sixth grade.

Up at the top of the riverbank, Sydney rocked back and forth on her bike. “Ready?”

Nate already stood in the river with his bike, the water up to the middle of the wheels. The water was low because it had been dry, which was good because when there was a lot of rain the river turned green and stuff grew on it. From farm runoff, my dad said.

Nate yelled, “Go! Go! Go!”

Sydney skidded down the steep bank—the closest thing to a hill around here—fighting with her handlebars as she tried to keep control through the mud. Her bike sent up a big spray as it hit the shallow water, and she shrieked. I followed her down and mud splattered all the way up to my face, and then the splash of water soaked my shirt. The day was the kind of hot that felt like it was sitting on you. The water wasn’t much cooler, but at least it was wet. I didn’t even think about itching.

As we hauled our bikes up to go again, Sydney said, “I can’t believe school starts next week.”

“Me neither,” I said.

“At least football is starting up,” Nate said. He chucked a clump of mud at me, but it went wide and splattered on Sydney’s arm instead. The handful of mud I threw at Nate missed him completely.

Sydney laughed. “You guys will never play ball with arms like that.”

“Watch me,” Nate said, and he hit my leg on his next throw.

It had been a good summer.

Sydney lived down the street from me and we’d been friends since I first moved to Ohio. We hung out a lot—riding bikes on the riverbank, playing video games and then cards on the front porch when her parents kicked us out of the house, striking at her brothers with water balloons when they were doing yard work. Usually it was just the two of us. Then Nate started showing up with his bike at the river. And sometimes when I was hanging out with Nate, we hung out with the other guys from school.

Nate popped up the front wheel of his bike, tipping his head back to look at the sky, which was as dark as a bruise. “Let’s go get slushies before it rains.”

At the gas station, we tracked in mud. “We’re swamp creatures,” Sydney said. She pushed back her hair with her muddy arm. It was coming out of her braid and fuzzed all around her face.

There weren’t any cars at the gas pumps. The day the tornado came through was also the first day of the Buckeye football preseason and the store was empty.

“Shoot,” Sydney said, heading to the counter. “The slushie machine is broken.” She looked at the guy at the cash register. “For real? That’s all I want. That’s all I want in the whole world. A slushie.”

“There’s ice cream in the back freezer.”

“I only do the slushies. Thanks anyway.”

I asked the guy if there had been any weather alerts, but he said he’d only been listening to the game. “Buckeyes up by fourteen already,” he told us. That’s how it is in Ohio. Everybody is always talking Ohio State University football.

“It’s going to be a blowout,” Nate said, cracking his knuckles, and I guess Nate knew the guy because they started talking about the game and then Nate’s grandparents.

“Excuse me,” I said, butting in, “but are you sure there isn’t even a watch out? Or a thunderstorm warning?”

All spring there had been tornadoes, the kind that busted out of the sky in the middle of the night. Invisible demons in the dark, roaring as they came to eat you, your house, your town. It got so bad everywhere that my grandmother, who lived in another state, followed our weather. Sometimes she called us before our town’s tornado sirens even went off. She called if it was the middle of the night. The weather was so bad that no one minded. The wail of tornado sirens is hard to hear when you’re inside a house, asleep, with the air conditioner running.

“Maybe,” the guy said. “Sorry about the slushies.”

Nate said, “We can find something at my grandmother’s.”

We rode our bikes farther down the empty roads to Nate’s grandmother’s storage units—the Storage-U—and she had Popsicles in the freezer in her office. They were the kind in plastic tubes that you freeze at home. Sydney read the ingredients on the box. Big blue clouds rolled in, fat and heavy.

It felt like before.

We ate fast.

The Storage-U was three long lines of cinder block buildings with red metal doors and three long gravel driveways. The office was a trailer near the road. Nate’s grandmother was working inside. After a while, she banged on the window and waved us away, and I shoved the empty Popsicle wrapper into my pocket and climbed on my bike.

“Go Bucks!” Nate, his teeth still around the plastic tube, peeled off toward his house with a wave, but I lived farther on, and Sydney a block beyond me. It was hot and soupy, but the wind that pushed in was cold.

Once Sydney and I made it to our street, it took us three minutes to get to my house. I knew that because the tornado sirens started to wail, and they wail solid for three minutes before turning off and then starting up again.

The sirens are loud. Piercing. The sound goes right through your body and down into your soul and rattles your earwax.

My mother stood out on the steps

of our front porch. My mom is neat and orderly, but right then she looked wild, with the wind blowing her hair so it covered her face. She yelled into the phone. “They’re here! She’s here. I’ve got them. I’ll get her into our basement.”

She stopped us from hauling our bikes up onto the front porch and we left them clattering down to the sidewalk behind us. We kept on our helmets and wet shoes. In the living room, the Buckeyes played silently in a little rectangle in the corner of the television. The rest of the picture was nothing but weather guys. Let me tell you this: no one interrupts the Buckeyes. If the Buckeyes are silent, it can only be a matter of life or death. “If you live in the warning box on the map,” the weather guy said, “you need to take shelter now.”

In the basement, my mom handed Sydney the phone and told her to call her parents. “Just so they know you’re here and safe. It was wild out there. They might not have heard me.” Mom turned on the weather radio. Dad was at work even though it was a Saturday. We sat in old lawn chairs. The futon was covered with suitcases.

Sydney asked, “What’s with all the suitcases? Are you going somewhere?”

“Mom’s going to China.”

“For real?” She looked at all the suitcases again. “Is she moving there?”

“It’s a business trip.”

“I leave next week,” Mom said. “I’m still trying to evaluate the best suitcase.”

“Wow, China. That’s awesome.”

Mom didn’t even know how long she would be gone. She said at least two months. There wasn’t anything awesome about it.

Mom offered us snacks. “We’ve got some stashed down here for occasions just like this.” She got some candy from a grocery bag hanging on an old coat tree.

“Mom! Come on. You can’t give Sydney that stuff.” I said it the same time Sydney said no, thank you. Polite. The way she always speaks to grown-ups. She’s so good at it my mother tells me I should talk like her.

Mom stuck the miniature candy bars in her pocket and I ran up the stairs where it was loud with rain and sirens and grabbed a bag of pretzels that was a brand I knew Sydney could eat and a two-liter bottle of root beer. Back down in the basement I asked her, “This okay?”

“Yeah,” Sydney said, taking the pretzels from me. “Thanks.”

Hail hit the small basement windows and the wind hollered. The lights browned out and then were gone, and it was just us, the storm that sounded like a military plane with its belly scraping over the roof of our house, and the weather radio.

Then it was after.

The street was filled with garbage and trash can lids and roof shingles and tree branches and lawn chairs. A couple of trees were down. My bike lay in the middle of the road. Sydney’s was just gone. Downed power lines lay across the sidewalk like giant black snakes. They hissed like snakes too.

Mom stopped us right on the front porch, her hands clutching tightly into my shoulder. She grabbed Sydney too.

“Not one step more. Those are live power lines. We’re not going anywhere near them. Let’s try heading out through the backyard.”

So that’s how we went, through the wet grass and through neighbors’ yards and across the street to Sydney’s house, where one of her older brothers, Dylan, came running toward us. He was yelling about Sydney’s bike.

“It’s in a tree! We found it in a tree! Come and see!”

The bike was caught in an oak tree one house down from Sydney’s. It’s a giant tree. Her bike hung up as high as the second story. “I wonder if I can see it from my bedroom,” she said as we stood looking up at it. The bike hung from its back wheel, twigs and branches and leaves all jammed through its spokes.

“Wow, Isaac,” she said, her head still tipped up, “you saved my life.”

“It was mostly my mom.” Some of the smaller branches creaked under the bike’s weight, and we hustled back.

“Still, though. Thanks,” she said, her eyes on the tree.

“Anytime.”

Mom said, “Let’s just hope it won’t have to happen too often.”

“I can totally agree with that.” Then Sydney hugged Mom and told her to have a good trip to China. She cut away from the tree and through her grass to her brother, and Mom and I went home through backyards again.

That night it was dark and hot and quiet and there were more stars in the sky than I had ever seen in my life. We sat out on the front porch. Mom and Dad sat in the rocking chairs but didn’t rock and I sat on the top porch step and looked up at the sky until my neck ached, and when I finally looked away all I saw were pricks of starlight.

I asked Mom, “Will you see the same stars over China that we do in Ohio?”

Mom said she didn’t know for sure. “I’m going to be a little farther south, so that changes some of the stars I might see. We’ll be in the same hemisphere,” she said, “so maybe it won’t be too different.”

“You should be sure to remember to take a look,” Dad said, “for scientific purposes.”

Would a person even notice if the stars in the sky were different? Even if you’d never thought about the stars or the sky or constellations before and if you were far away from home, would you be able to look up to a different night sky and see that it wasn’t the same as yours? Would you know right away? Maybe it would be the kind of thing that even though you’d never thought about it, you’d recognize it right away, like how toilets flush the other way in Australia. You’d notice that, right, if you were visiting Australia? But what if you didn’t notice? What if everything was different and you didn’t even know?

The rocking chair rocked once as Mom got off and came to sit with me on the step. She looked up at the sky with me. It’s a big sky right here in Ohio. There’s nothing that gets in the way of it.

Mom told me to look at the moon. A hazy white hook of a moon sat in the sky above the oak tree that had caught Sydney’s bike. “The moon will be the same.”

CHAPTER 2

THE TORNADO PEELED away the school’s cafeteria roof like an old Band-Aid and blew out walls, turning the rain into solid bricks. Debris beat up fields of feed corn and soybeans and busted cars and killed a couple of pigs out at Tyler’s dad’s pig farm. Some of Nate’s grandmother’s storage units were blown apart. Nate said every now and then someone called saying they found a chair or a table or a grill out in a field, wondering if maybe it was from their place.

Sydney’s dad got her bike down from the tree. She said her handlebars were wonky and the wheels were bent and her dad was going to try to fix it, but she wasn’t in a hurry because she liked the proof of what happened, of us out-biking the tornado and then her bike stuck up in a tree.

We lost power for a couple of days after the storm and it was hot, so I started sleeping in the basement. Once the power came back on I didn’t bother going back up.

The basement is peaceful. It has three high, rectangular windows, and when the sun shines through late in the morning it’s almost as bright as any room upstairs. There’s just a radio and the futon (which is actually really comfortable) and some old lawn furniture and an old TV that no one ever bothered to plug in. I added a clothes basket of clothes and my computer.

When the power came back on, Mom said she thought I should go back upstairs to my bedroom. “How long are you staying down there?”

“I don’t know. I like it. It’s cooler than the rest of the house.”

Two days before school started we drove Mom to the airport. We waited around with her until we had to say goodbye at security. “I can’t believe it,” she said, slinging her arm around my shoulders. “Look at you, getting so tall.”

“I can’t believe you’re going to China.” I didn’t know anyone who went to China. Kids went to Disney and amusement parks and on cruises, but no one went to China.

“Me neither, kid,” she said, shaking her head. “Remember when we moved out here?

To Ohio?”

“Yeah.” Of course I did. Three years ago Mom and I drove out in one car, Dad in the other, and even though I always sat in the back seat because that’s where kids are supposed to sit, Mom let me move up to the front so I could pass her snacks and help her with the GPS and read signs. Every time we crossed a state line it was a race to see who could touch the windshield first. I won two out of three, but only because I wasn’t driving.

“I couldn’t imagine living in Ohio either, then, but here we are. I’m sure I’ll figure it out. One foot in front of the other.”

I had her laptop bag over my shoulder. I started to itch my neck, under the strap. Mom grabbed my hand and tucked it into a fist.

“Stop,” she said. Then she went through her list for me. Again. She’d been doing it all day. “Remember your medicine. Keep your grades up. Wear your helmet when you ride your bike. We’ll video chat, okay?” She smiled. “And maybe don’t go so far from home when storms are coming in. I think you took ten years off my life.”

“I did not.”

“You did. Trust me. Leaving you now is way easier than when I was looking for you and Sydney to finally come down the street.”

Then it was hugs, and Mom and Dad kissed, and Mom said, “Take care of each other, okay?” and she headed through the metal detector. Dad and I got soft pretzels and sat by a window and waited for Mom to text us that she was boarding. We watched other planes take off. I pretended each one was hers. It was night and the planes were silver in the city’s lights. They aimed up at the dark sky and then they were faraway blinking lights and then gone and they might as well have been stars.

She was flying to San Francisco and then Japan and then China. I pictured it like a cartoon, with the earth spinning one way and the plane going the other.

When we got home it was late, and Dad and I were hungry and we made fat peanut butter sandwiches. I stuffed chocolate chips in mine. We drank root beer. My teeth felt fuzzy from the sugar. The only light in the whole house was the yellow light above the sink. The world felt very small, just me and my dad.

Itch

Itch